Photo: The Swedish History Museum (CC BY 2.0)

Photo: The Swedish History Museum (CC BY 2.0)

The Stockholm Bloodbath of 1520

In November 1520, the political heart of Stockholm became the scene of one of the most consequential acts of violence in Scandinavian history. Over three days, spproximately one hundred Swedish nobles, clergymen, and citizens were executed in Stortorget, the central square of Gamla Stan. The massacre, later known as the Stockholm Bloodbath, was intended to secure Danish rule over Sweden. Instead, it ignited a rebellion that ended the Kalmar Union and gave birth to an independent Swedish state.

- Date: 8–10 November 1520

- Location: Stortorget, Gamla Stan

- Ordered by: King Christian II of Denmark

- Victims: Nearly 100 Swedish nobles, bishops, and citizens

- Consequence: Sparked revolt led by Gustav Vasa

The Road to Catastrophe: The Kalmar Union Under Strain

At the time of the executions, Sweden was part of the Kalmar Union — a political alliance formed in 1397 that united Denmark, Norway, and Sweden under a single monarch. In theory, the union promised stability and collective strength. In practice, it was marked by recurring tensions, especially between the Danish crown and the Swedish nobility.

Swedish elites resented Danish dominance, particularly when royal officials interfered in local governance or trade. The Baltic economy was deeply intertwined with Hanseatic merchants, and control over customs, ports, and fortresses was not merely administrative — it was financial power. Throughout the 15th century, Sweden experienced repeated uprisings against Danish kings. By 1520, the union had become less a partnership and more a contested occupation.

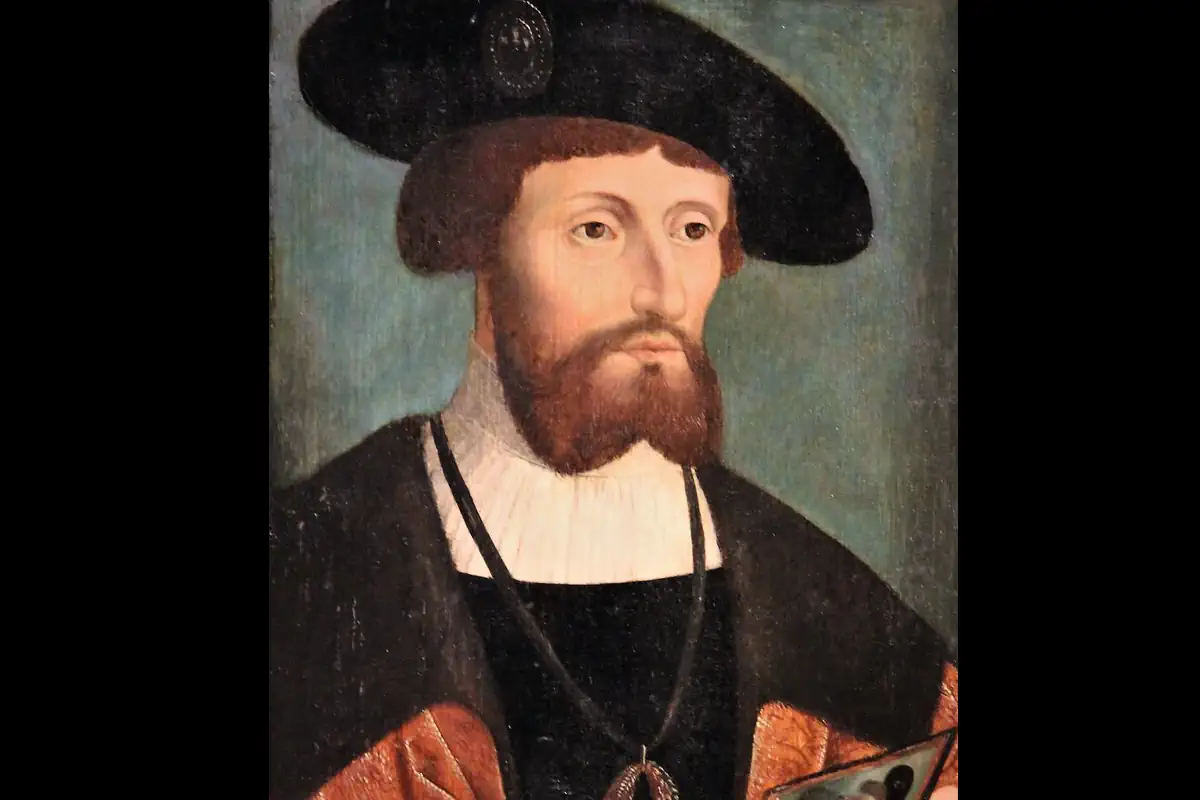

Christian II of Denmark launched a military campaign to reassert control over a kingdom that had repeatedly resisted centralized rule. After defeating Swedish forces, he entered Stockholm and was crowned king in Storkyrkan Cathedral on November 4, 1520. Publicly, he promised reconciliation and stability. Privately, he prepared to eliminate his political opponents.

The Legal Trap: Heresy as Political Weapon

Shortly after his coronation festivities, Christian invited leading Swedish nobles and clergy to a grand banquet. Many had opposed him; some had even fought against him. Yet they attended under assurances of amnesty.

Days later, the tone shifted dramatically. The guests were arrested and accused of heresy — a charge engineered through the reinstated Archbishop Gustav Trolle, who claimed that earlier resistance against him had constituted rebellion against the Church itself.

By framing the conflict as heresy rather than political dissent, Christian II transformed a matter of state into a religious crime. Under canon law, heretics could be executed without violating prior promises of pardon. The maneuver gave the appearance of legality to what was, in effect, a calculated purge of Sweden’s political leadership.

It was a ruthless act of statecraft: the language of faith used to nullify political compromise.

The Executions at Stortorget

From November 8 to 10, 1520, executions were carried out publicly in Stortorget — the same square that had served for centuries as Stockholm’s marketplace and civic center. Bishops, knights, noblemen, city officials, and ordinary citizens were beheaded before assembled crowds.

Bodies were later burned or disposed of in the harbor. Even individuals who had not actively resisted Christian were among the victims. The betrayal was total. What had begun as a coronation celebration ended in bloodshed, permanently staining the political memory of the square.

The massacre was meant to intimidate Sweden into submission. Instead, it exposed the fragility of Danish authority.

From Massacre to Martyrdom

The Bloodbath did not secure Christian II’s rule — it destroyed it. News of the executions spread rapidly across Sweden, fueling outrage and fear. Families of the executed nobles became symbols of injustice, and the event quickly transformed from a punitive action into a narrative of martyrdom.

Among those affected was Gustav Eriksson Vasa, whose father had been executed during the Bloodbath. Within months, he began organizing resistance in Dalarna. What started as regional defiance evolved into a national uprising.

By 1523, Gustav Vasa entered Stockholm as king. The Kalmar Union collapsed, and Sweden emerged as an independent kingdom. The Bloodbath, intended to consolidate empire, had instead catalyzed the formation of a nation.

Memory, Myth, and Nation-Building

The Stockholm Bloodbath became more than a historical event — it became a foundational narrative. Gustav Vasa skillfully used the massacre as propaganda, portraying Danish rule as tyrannical and illegitimate. The executions provided moral justification for rebellion and helped unify disparate regions under a shared cause.

In this sense, the Bloodbath occupies a paradoxical place in Swedish history. It represents brutality and betrayal, yet it also marks the symbolic beginning of political independence. The memory of November 1520 would echo through centuries of Swedish state-building.

Today: A Quiet Square, A Violent Past

Visitors to Stortorget today encounter colorful façades, cafés, and seasonal markets. Yet beneath the cheerful atmosphere lies a layered past. A small plaque commemorates the victims of 1520, and several surrounding buildings date to the period of the executions.

The square that once served as Stockholm’s civic stage — anchored by the urban vision first consolidated under Birger Jarl — became, in 1520, the crucible in which Swedish independence was forged.

Bishop Hans Brask’s name lives on in the Swedish word “brasklapp,” meaning a discreet disclaimer. Forced to sign a document supporting punishment against Archbishop Gustav Trolle, he secretly inserted a note beneath his seal:

“To this I was compelled and forced.”

The hidden message may have saved his life during the Bloodbath — a small act of caution in an era defined by perilous politics.

Visit Info

![]() Stockholm bloodbath

Stockholm bloodbath

![]() Stockholms blodbad

Stockholms blodbad